Over the past six years, two Egyptian Vultures—Fangueiro and Arribas—have been tracked via GPS from the moment they left the nest (or were returned to the wild), offering a rare and invaluable glimpse into the migratory lives of this globally endangered species. Their journeys have spanned tens of thousands of kilometres, crossed continents, and revealed critical insights for conservation. This is their story.

Fangueiro: A vulture’s second chance

Fangueiro’s life began with hardship. Found weak in Fão, Portugal, in the autumn of 2019, the young vulture showed signs of having suffered severe hunger in the nest, leading to stunted and damaged feather growth. He was rescued and transferred to a rehabilitation centre, where he underwent multiple operations and treatments, including the rare procedure of feather transplants—implanted feathers from donor birds that would allow him to fly again.

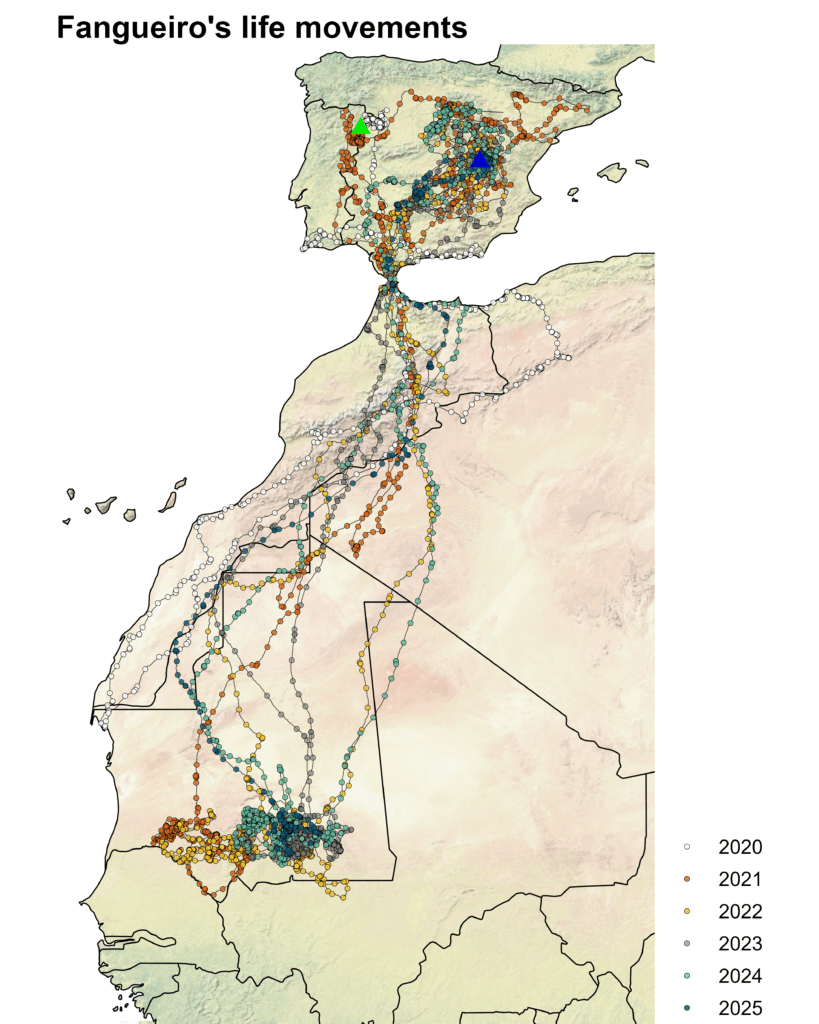

After nearly a year of recovery, Fangueiro was released on 13 July 2020 in the Douro region under the LIFE Rupis project. Tagged with a GPS transmitter, he was now ready to return to the wild as an immature male Egyptian Vulture.

Since then, Fangueiro has travelled more than 12,600 km. In his first year post-release, rather than undertaking the typical journey across the Sahara Desert, he flew only as far south as the Banc d’Arguin in northern Mauritania—a renowned Ramsar site best known for its waterbird colonies and wintering populations of Siberian waders. After just two months in Africa, he returned to the Iberian Peninsula—an unusual pattern that suggests he wasn’t ready for the full crossing and opted for a safer route.

But in the years that followed, Fangueiro settled into a more regular migratory rhythm, travelling to the Sahel and returning four times so far. His wintering grounds in southern and southeastern Mauritania are particularly significant: this region is traditionally used by Egyptian Vultures from Western Europe, along with other migratory raptors like Black Kites and Booted Eagles. Yet curiously, Fangueiro hardly ever returned to the Douro, where he was released.

This behaviour supports the idea that he likely hatched in Castilla-La Mancha, west of Madrid in Spain, before being rescued as he spends most of his time there when he is back in Europe. Egyptian Vultures are highly philopatric, meaning they tend to return to breed in or near the area where they were born. Since 2023, Fangueiro has been increasingly frequenting this region, which hosts Spain’s third-largest breeding population of the species—about 14% of the national total. As of now, Fangueiro has not yet bred, but his consistent presence in this area suggests he may be preparing to do so.

Arribas: The long-distance champion

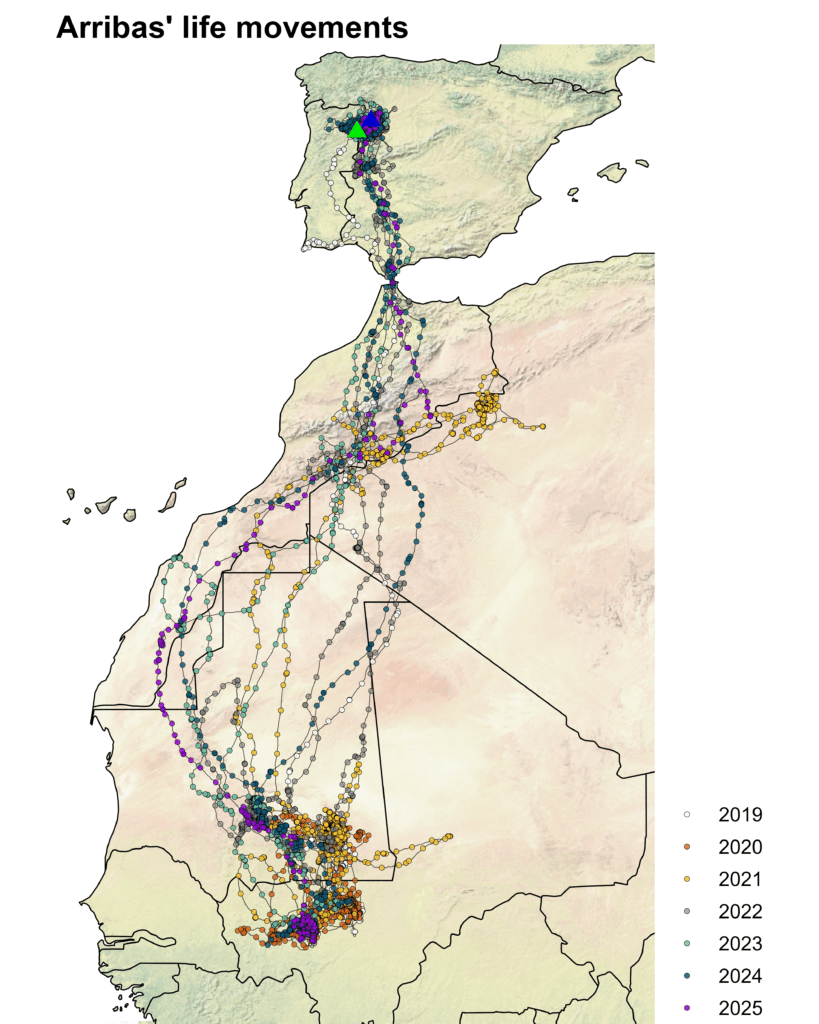

Unlike Fangueiro, Arribas was tagged as a juvenile in the nest in Portugal in August 2019. Though its sex is still unknown, one thing is clear: this bird has been remarkably mobile, covering over 143,500 km in just six years.

After fledging, Arribas followed the traditional route of young Egyptian Vultures and migrated to Sub-Saharan Africa, wintering in the same region of southeastern Mauritania as Fangueiro. But instead of returning to Europe in 2020, Arribas stayed put, spending the entire year in Africa. This is not unusual—immature Egyptian Vultures may remain in Africa for more than three years before they reach maturity and begin the return migrations to Europe.

In 2021, Arribas ventured north, reaching the border region between southeastern Morocco and Algeria, though never crossed back into Europe. But from 2022 onwards, something shifted: Arribas began a consistent pattern of migration back to the Douro International region, where it hatched and was tagged.

This return marks a critical milestone in the life of an Egyptian Vulture: the moment it begins to reconnect with its natal territory, potentially gearing up to breed in the coming years.

Gaps in the signal

At one point during tracking, it seemed that one of the vultures had died—its GPS tag stopped transmitting while in Morocco. Weeks passed with no updates, and the worst was feared. But then, unexpectedly, the bird reappeared—already in Spain. Though the story itself may not warrant headlines, it highlights a major challenge in tracking: the limitations of GSM networks in remote areas, especially in Africa.

Egyptian Vultures often spend long periods in vast, uninhabited landscapes where mobile signal is non-existent, meaning their tags can’t transmit data for weeks or even months. Sometimes, tags never reconnect at all, leaving conservationists in permanent doubt about the bird’s fate. But in many cases, once the vulture returns to more urbanized or connected areas, the GPS devices transmit a backlog of stored data, catching us up on where they’ve been.

What six years have taught us

Tracking Egyptian Vultures like Fangueiro and Arribas over several years has provided critical insights into their lives and the risks they face. These birds are unique among raptors for their long immature period—they typically don’t begin breeding until at least five years old. Monitoring their journeys from a young age helps scientists understand juvenile survival – as they are long-lived birds, their survival increases with age as birds get wiser. Particularly in the first year, mortality can be very high, when they are naive and do not know their way to or from Africa.

For instance, vultures from the Balkans often drown in the Mediterranean Sea during their first migrations, because they don’t yet know the safe land-crossing via the Bosphorus. Many attempt to fly from Greek islands directly across the sea and perish. Arribas and Fangueiro may have avoided this fate simply by being born in the West: both ended up at one point in Sagres, the southwestern tip of Portugal. It’s a common destination where many juvenile raptors that do not know the way to Africa via Gibraltar end up lost and unfamiliar with the proper crossing routes. With no land in sight, they are forced to turn back and try again.

Tracking data helps us identify hot spots, allowing conservation efforts to be more targeted. Once in Africa, vultures roam across huge areas where legal protections are weaker and threats like poisoning, electrocution, and even direct persecution for traditional medicine practices pose serious risks. Consistent use of southeastern Mauritania by vultures tagged in Spain, France, and Portugal suggests that this region is a key non-breeding area for the entire western population—information that is already helping to shape conservation priorities.

Tracking also helps us pinpoint the start of breeding attempts, so local teams can monitor and protect nests. It allows for a better understanding of how non-breeding birds use feeding areas in both breeding and wintering ranges.

In fact, the data from Fangueiro and Arribas have already been used in research, including Master’s theses and other scientific studies, and continue to inform conservation strategies across Europe and Africa.

Looking ahead

Fangueiro and Arribas are still flying, still teaching. Their paths may diverge, but both have proven invaluable in uncovering the hidden geography of a species in decline. Through the data they transmit, we are learning not just where Egyptian Vultures go, but what they need to survive.

Their journeys remind us that protecting a migratory species means protecting entire flyways, across dozens of countries and habitats. And as these two young vultures approach breeding age, the next chapter in their lives—and in our understanding—may soon begin.