Across several regions of France, poison continues to be used to illegally kill protected wildlife. Wolves are usually the intended target. But they are not the only victims. Vultures and other scavengers frequently consume poisoned bait and die as collateral damage.

Recent cases suggest this is not a series of isolated incidents. It reflects a pattern of deliberate environmental crime and an ongoing problem of weak enforcement and limited accountability.

Under French law, destroying a protected species is punishable by up to three years in prison and a fine of 150,000 euros. Yet convictions remain rare.

A method designed to avoid detection

Poisoning has become one of the most common methods used to kill wolves illegally. It is discreet, inexpensive, and relatively easy to deploy.

In 2022, a farmer in the Drôme admitted to poisoning a wolf and burying its body. He had infiltrated a wolf/lynx network of the French Office for Biodiversity to gather information for poaching. He ultimately received a one-year suspended prison sentence and a five-year hunting ban. The wolf’s body was never recovered.

The case led to a conviction largely because the suspect was already under police surveillance in another investigation. Such circumstances are rare.

Conservationists estimate that only around ten per cent of wildlife that dies in nature is ever found. Wolves tend to hide before death, and scavengers quickly remove remains. Without a body or physical evidence, investigations rarely move forward, and prosecutions often do not follow.

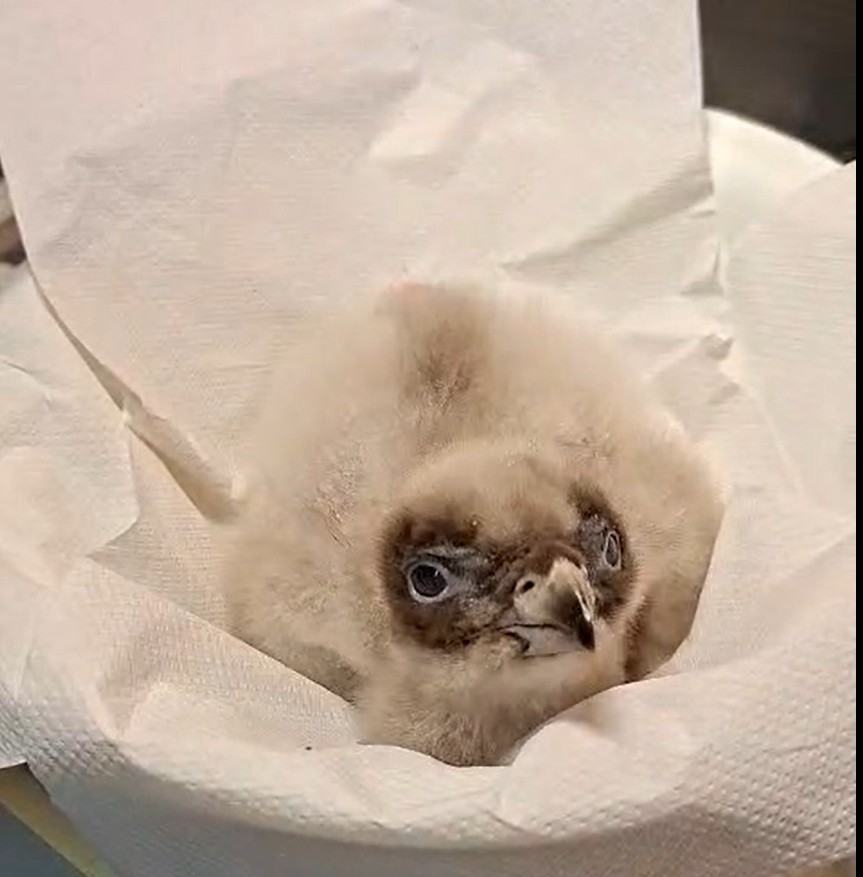

Collateral damage to protected species

Poison is not selective. Baits intended for wolves are frequently consumed by vultures and other birds of prey.

Between 2021 and 2024, at least 143 raptors in France were identified as having died from poisoning. In 2024 alone, 112 dead raptors were discovered, with at least 27 confirmed poisoning victims, amounting to roughly 30 per cent of the carcasses found that year, while 14 per cent had been shot.

In spring 2025, Vautours en Baronnie conservationists tracking vultures by GPS located eight dead birds (four Griffon Vultures, two Cinereous Vultures and two Egyptian Vultures), all protected species, near poisoned bait in the Drôme. The bait had been soaked in banned pesticides. An investigation was opened and remains ongoing.

Most poisonings involve carbamate pesticides such as carbofuran or aldicarb, substances banned in the European Union since 2008 and 2007 because of their extreme toxicity. Even very small quantities can be lethal. Just a few granules of aldicarb, roughly equal to the size of an aspirin tablet, can kill 21 people. Their continued use in wildlife crime raises serious questions about illegal supply chains and regulatory oversight.

Rare convictions and a sense of impunity

Although investigations are generally opened when poisoning is suspected, they rarely result in convictions. Toxicological analysis requires time, expertise and resources. Carcasses may decompose before examination, and poison often leaves limited forensic traces. Enforcement officers are not always specifically trained to detect or secure this type of evidence.

As a result, successful prosecutions usually depend on offenders being caught in the act or captured on camera. For many conservation professionals, this creates a growing sense of impunity. When crimes repeatedly go unpunished, deterrence weakens.

Strengthening enforcement capacity

In response to rising wildlife crime, French authorities established a specialised unit of environmental judicial officers in 2025. Plans are also underway to create a poison detection canine unit.

At the same time, the Wildlife Crime Academy has begun training French investigators, prosecutors and environmental officers in toxicological crime response and inter-agency coordination.

These are important developments. But new units and training programmes will only make a difference if they are supported by sustained political will and adequate resources.

Poisoning is not a minor regulatory violation. It is a serious environmental crime, one that undermines biodiversity protection and the rule of law.

Addressing it effectively requires consistent enforcement, specialised expertise and a clear signal that wildlife crime will not be tolerated.