Long before science highlighted vultures ecological importance, cultures around the world had already developed deep symbolic connections to these incredible raptors. From symbols of life and renewal to dark omens, vultures have played many roles in myth, religion, and rituals in human history.

Vultures have long held a complex and fascinating place in human culture, embodying a wide range of symbolic meanings across time and continents. In many ancient societies, these birds were revered as protectors, purifiers, and spiritual guides. Yet, in the modern world, especially in western countries, vultures often bear a negative reputation, associated with death, filth, and bad omens.

Sacred protectors and purifiers

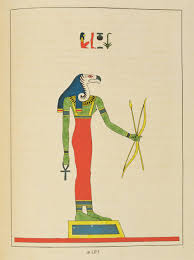

Historically, vultures enjoyed widespread reverence. In ancient Egypt, vultures symbolized motherhood, protection, and divine authority. The goddess Nekhbet, often depicted with a vulture head, embodied a nurturing guardian. The hieroglyph for “mother” was symbolized by a vulture, and female rulers wore vulture-shaped headpieces.

On the other side of the world, in Andean cultures, particularly among the Inca and Quechua, condors occupied a sacred place. They symbolized renewal, transformation, and balance within nature’s life cycle. They were seen as rulers of the upper world and messengers between humans and gods. Myths describe the condor as a creature that can see both life and death from above.

Today, in Tibetan Buddhism, vultures still play a crucial spiritual role during the “Sky burial” ritual. Rooted in Vajrayana Buddhism, this ritual sees the human body offered to vultures as a final act of generosity. The flesh is consumed by the birds, nourishing other living beings.

Omens and instruments of divine retribution

In ancient Greece, vultures played a much dark role, enforcing divine will. In both myths of Tytus and Prometheus, vultures feasted on the Titans’ bodies as punishment for testing the gods and defying their will.

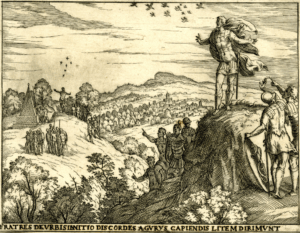

Both in Greek and Roman cultures, vultures were also associated with the god of war Ares/Mars. They often accompanied armies and cleared the aftermath left on battlefields. Lastly, vultures, like many birds, were regarded as omens. In the myth of Romulus and Remus, for example, the number of vultures seen by each of the twins indicated which one of them would succeed in founding a new empire.

The Biblical and Christian traditions reinforced the negative image of vultures, associating them with death and decay. They were also often considered foretellers of misfortune. A vision shared with many African folklores that blame vultures for misfortunes and diseases. In a more widespread modern narrative, vultures scavenging behaviour made them easy metaphors for greed, cowardice, or corruption.

Cultural challenges in vulture conservation communication

Protecting vultures is not only a conservation effort but also a cultural challenge. Understanding vultures cultural significance offers valuable insights for conservation. Their journey from sacred symbols to misunderstood scavengers reflects broader human attitudes toward death and nature’s cycles.

Today, amidst global vulture declines, changing their reputation is a crucial part of conservation strategies. Highlighting vultures’ vital ecological role in maintaining healthy ecosystems, building local pride around them and helping people reconnect with them can help shift perceptions and foster coexistence. With informed communication and respect for cultural contexts, we can honour vultures as indispensable stewards of our ecosystems and cultural heritage.

Sources

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Nekhbet

https://doi.org/10.14795/j.v3i4.204

https://thewondernepal.com/articles/the-tradition-of-sky-burial-in-mustang-nepal

https://www.tibettravel.org/tibet-travel-guide/sacred-vulture-in-tibet.html

https://worldbirds.com/vulture-symbolism

Benson, 1996; JSTOR Daily – Rose, 2024

https://smokymountainnews.com/archives/item/25315-cherokee-thought-buzzards-possessed-powers