The recent death of a young Egyptian Vulture (Neophron percnopterus) named Kushka in Yemen, thousands of kilometres from where she hatched in Bulgaria, highlights one of the most persistent and cross-border threats facing migratory scavengers today: poisoned baits.

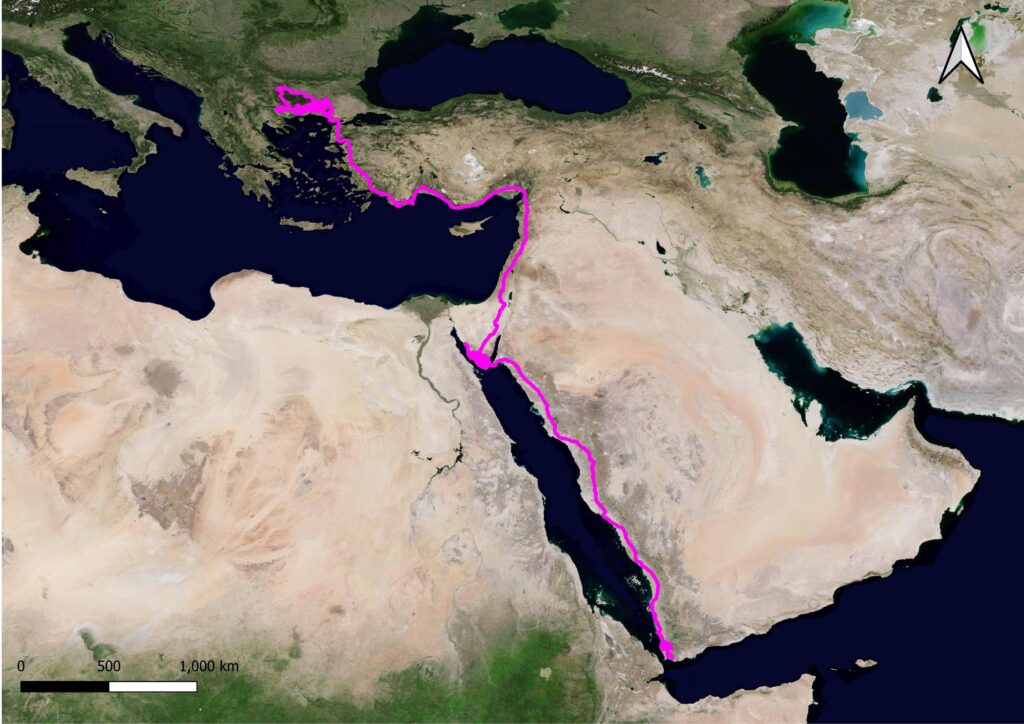

Kushka was part of the Class of 2025 at the “Egyptian Vulture School” in Bulgaria, a population reinforcement effort led by the BSPB to support this globally endangered vulture species. Taken from a wild nest due to late hatching, she was hand-reared at the Wildlife Rehabilitation and Breeding Centre run by Green Balkans, then fitted with a GPS transmitter before release to monitor her journey. Like many Egyptian Vultures from southeastern Europe, she migrated towards the Middle East to spend the winter. But her migration came to an abrupt end in western Yemen.

A silent signal

The first sign of trouble came via Kushka’s GPS tag, which showed she hadn’t moved for hours, usually a clear indication that something was wrong. Confirming what had happened, however, seemed nearly impossible. Yemen’s civil war has made large parts of the country extremely dangerous and hard to access, posing serious challenges to conservation work on the ground.

Against all odds, clarity arrived through a WhatsApp message. A local resident found the bird, noticed a phone number on the transmitter, and reached out. Through extended conversations in Arabic, with the help of Google Translate, conservationists were able to piece together what had taken place.

A goat carcass, poisoned with consequences

According to the resident’s account, a local farmer had poisoned a goat carcass to kill stray dogs that had been preying on livestock. But poisoned baits don’t discriminate. At least five Egyptian Vultures of varying ages fed on the carcass and were poisoned, including Kushka.

Using poison to deal with predators is a widespread practice in the region. While some farmers rely on direct shooting, many opt for poisons, often without grasping the broader impact. These toxins endanger not just wildlife, but also livestock, domestic animals and human health.

A high-risk wintering ground

Western Yemen serves as a critical wintering area for Egyptian Vultures migrating from different regions, including the Balkans, eastern Turkey, the Caucasus, and Central Asia. So when poisoning happens in this part of the world, the fallout can be felt across continents.

From a conservation standpoint, this makes the threat particularly severe. A single local act can have consequences on a population level, across an entire migratory flyway.

The broader impact on conservation efforts

Kushka’s death is a major loss for the Egyptian Vulture conservation work in Bulgaria. Reinforcing the population depends not only on captive breeding and successful release, but on ensuring birds survive their migratory journeys and the time spent in their wintering grounds, areas often beyond national conservation reach.

Nonetheless, the tragic event has brought valuable insights. Thanks to the actions of the local resident who reported the incident, conservationists have been able to better understand threats in a region that’s rarely studied and notoriously hard to reach. This kind of local cooperation is essential to shaping more effective international strategies.

Kushka’s death, along with those of at least four other vultures, drives home a key point: poisoned baits know no borders. They not only kill the intended targets, but also strike down rare and protected species that depend on coordinated, long-term international conservation efforts.