A recently published study sheds light on the factors influencing nestling sex ratio variation in Egyptian Vultures (Neophron percnopterus). With a long-term assessment of populations from Spain’s mainland, the Balearic and Canary Islands over 30 years (1995-2021), authors found that insularity influences offspring sex ratio, corroborating the island syndrome. Although no sex bias was found at the population level, two trends were observed: a nonsignificant female-biased offspring ratio (0.47) in Spain’s mainland and a male-biased ratio (0.55) in the Canary Islands.

Determining offspring sex variation in avian species

Understanding the ecological and evolutionary processes of a species requires long-term analysis. Although sex allocation has been studied over the last century, few studies relied on long-term monitoring data. Sex ratio can be biased by parental manipulation and differential egg or chick mortality (due to environmental conditions, siblicide or parent influence on feeding). It is categorised as primary (proportion of males over females at fertilisation) or secondary (at hatching). The authors have only analysed the secondary category.

According to Fisher’s sex allocation theory (Fisher, 1930), the sex ratio tends to be 1:1 in different species and populations. However, the theory does not consider the variance of parental investment in rearing females vs males in species that show sexual dimorphism, which is the case for many raptors. As females tend to be larger than males, raising a female requires considerably more effort and investment from its parents. Environmental conditions during breeding influence variations in offspring sex ratio; for instance, poor years in terms of food availability are often associated with a higher production of males. Younger pairs, with less experience, also tend to raise males more often, and the breeding timing may also affect offspring sex ratio, with females being produced at the beginning of the season and males towards the end, or vice-versa, depending on the species. Therefore, parents tend to favour a “greater investment in the sex that maximises their fitness” (Gómez-López et al.)

How insularity influences nestling sex ratio variation in Egyptian Vultures

Spatial differences can influence unique traits in different populations of the same species. The island syndrome phenomenon depicts how island populations have different morphological, demographical, behavioural, physiological and ecological characteristics compared to mainland populations. These factors influence the population dynamics and long-term survival. Also, island populations tend to have less migration of individuals from abroad, leading to populations with lower genetic diversity, which are more vulnerable to environmental changes.

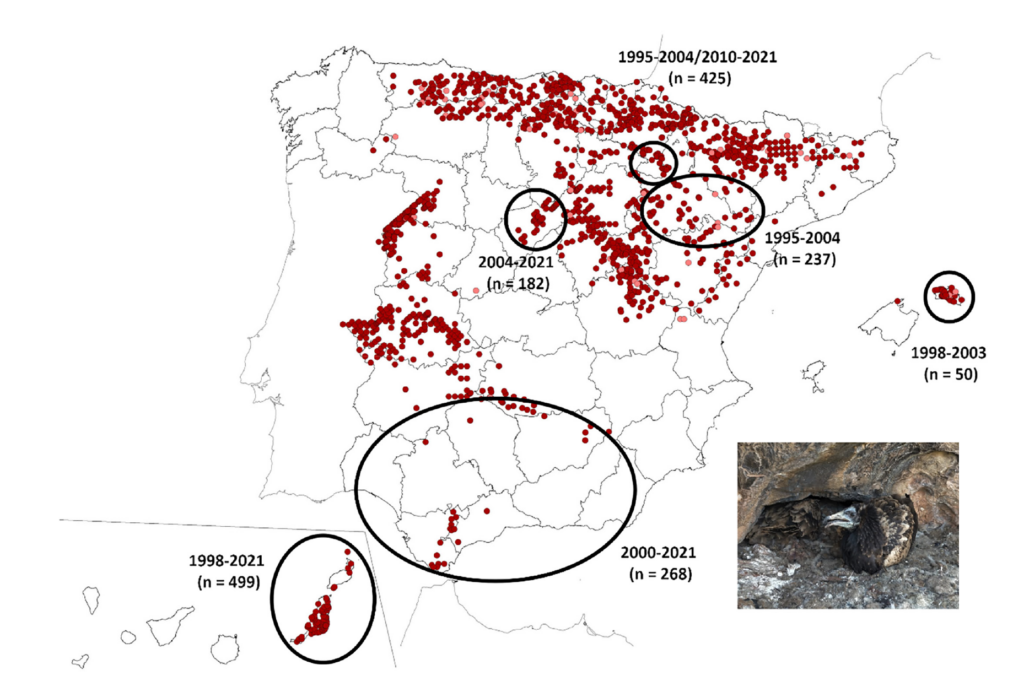

Factors affecting offspring sex variation are multiple and complexly interrelated. To understand the influence of insularity in the Egyptian Vulture populations, fieldwork was carried out during breeding seasons to detect and identify territorial individuals. Data collected throughout the season includes parental age, breeding phenology, brood size (number of hatchlings), hatching order, type of breeding unit (pairs vs trios), and spatial and temporal variability. They have also analysed how sex ratio patterns are influenced by season and interannual changes, like food availability, weather conditions and population density.

Breeding regions analysed in the study included peninsular Spain, Fuerte Ventura and Lanzarote (Canary Islands) and Menorca (Balearic) © Goméz-López et al.

Main results

The overall sex ratio of Egyptian Vulture nestlings was 1:1, remaining stable over the years. However, it was slightly female-biased in peninsular Spain compared with the Canary Islands, where it was significantly male-biased.

Gómez-López et al.

Insularity factors affecting sex ratio variation

The age composition of breeding individuals seemed to have affected offspring sex variation, a factor linked with insularity, as it varied between the mainland and the islands. With almost no subadult breeders in peninsular Spain, in the Canary Islands, where the population reached 400 individuals recently, the number was relatively high (10%). Less experienced individuals may produce the less costly sex, males in this case. The occurrence of subadult breeders can be linked with a higher survival rate of young birds on the islands. Sedentary individuals avoid several threats during migration, and the many conservation actions ongoing in the islands, such as supplementary feeding stations and minimisation of human-related mortality factors (poisoning, collision with power lines), may also increase survival rates.

In the Canary Islands, although the offspring sex ratio is male-biased, adult sex ratio has been reported to be 1:1. With an unbiased sex ratio in adults, mortality rates during nestling and the immature stage can be male-biased, possibly due to behaviour and foraging patterns. A higher territorial prospection with large-scale movements occurs more with males, exposing them to greater threats. Regarding foraging habits, females relied more on supplementary feeding stations, and males visited farms more often, which increased exposure to intoxication by illegal wildlife poison or lead. Authors suggest that the male-biased mortality among immatures “could be ultimately compensating for offspring biases so that the adult sex ratio would not reflect early-biased sex ratios”.

The effects of food availability

After the mad-cow disease, which led to strict sanitary regulations for removing domestic livestock carcasses that reduced food availability for scavenger populations, the offspring sex ratio was male-biased. In addition, the possibility of a second nestling being a male in double broods was also more significant after the regulations were implemented. In double broods, a significant bias was also found in the Canary Islands, with a tendency for two-male broods instead of two-female broods. According to the authors, there was no repeatability in offspring sex for trios in the Canary Islands. Still, curiously, one female-female-male trio had a strong bias towards males, having produced consecutively males for a period of nine years.

Although a male-biased pattern was observed after the implementation of regulations following the mad-cow outbreak, livestock analyses were considered by the authors as a very general proxy to estimate food availability, difficult to quantify. Firstly, measures were not taken equally across mainland Spain making it hard to compare, and secondly, because it considers livestock only, and Egyptian vultures only partially depend on domestic livestock carcasses. In addition, regional and local trophic variability may affect populations differently; for instance, in the eastern Canary Islands, despite a higher number of livestock, wild prey availability is lower given the extremely arid conditions. In these areas, producing the less costly sex might be a better strategy for the local population.

The remaining variables, including brooding size and variation, did not appear to affect the offspring ratio. Nonetheless, the study shows that insularity affects sex ratio variation in Egyptian Vultures due to factors that affect island and mainland populations differently.

Source:

Gómez-López, G., Sanz-Aguilar, A., Carrete, M., Arrondo, E., Benítez, J. R., Ceballos, O., Cortés-Avizanda, A., de Pablo, F., Donázar, J. A., Frías, Ó., Gangoso, L., García-Alfonso, M., González, J. L., Grande, J. M., Serrano, D., Tella, J. L., & Blanco, G. (2023). Insularity determines nestling sex ratio variation in Egyptian vulture populations. Ecology and Evolution, 13, e10371. https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.10371