A new tracking study covering most of the global Egyptian Vulture distribution reveals that more Egyptian Vultures are dying in eastern Europe and the Middle East while surviving better in Sub-Saharan Africa, with approximately half of the deaths being human-induced. The new research, published in the Journal of Animal Ecology this week, was led by Evan Buechley (International Program Director for HawkWatch International), Ron Efrat (PhD candidate at the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel) and Steffen Oppel (Conservation Scientist at the RSPB).

Methods

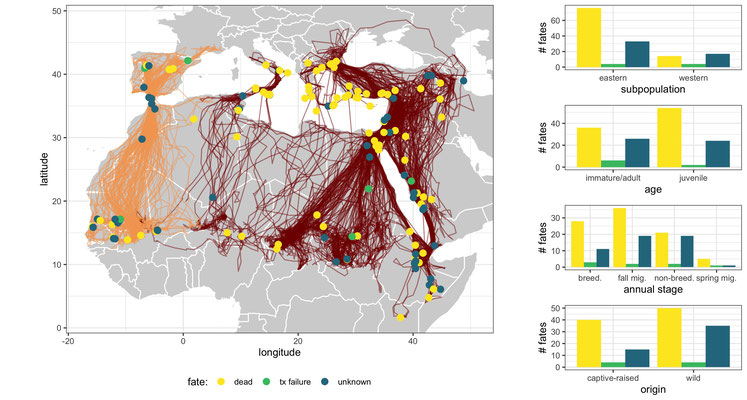

The study involved compiling and analyzing tracking data from 220 Egyptian Vultures fitted with transmitters since the early 2000s to study their movements and eventual fates, with the study area covering approximately 70% of the species global distribution, from Portugal in the West to Iran in the East, and from Russia in the north to Kenya in the south.

The fates of the birds were determined through a combination of direct observations (such as when a dead bird could be recovered and cause of death identified) and by assessing patterns in the tracking data (for example, if data transmission stopped over water it was assumed the bird probably drowned). The analysis also accounted for when the fate of the bird could not be determined definitively, perhaps due to transmitter failure or other cause.

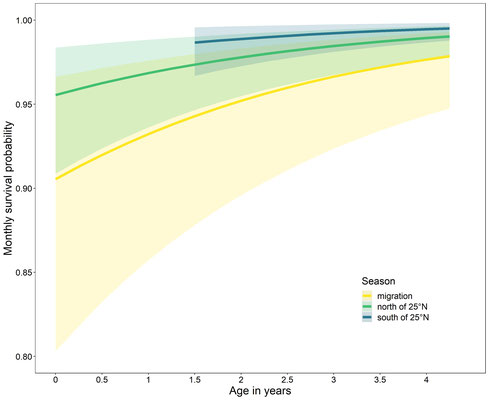

The analysis also compared the survival rates of the vultures when they were migrating compared to when they were stationary, as well as among breeding populations and when the birds were in their breeding or non-breeding ranges. Age-related differences in survival were also tested for.

Results

The main findings were as follows:

- Survival was lower during months when a bird migrated compared to stationary periods, indicating that there is a direct survival cost associated with long-distance migrations.

- Adult birds had higher survival on non-breeding grounds in Sub-Saharan Africa compared to breeding grounds in southern Europe, the Caucasus, and the Middle East.

- Egyptian Vultures originating from western Europe, where population trends are more positive than further east, had overall higher survival rates throughout the year.

- The incidence of mortality over the Mediterranean Sea was high (particularly for juveniles attempting their first autumn migration), while very few vultures died in the Sahara Desert, perhaps illustrating that what constitutes an ecological barrier varies among species.

- More mortalities were recorded further north, which contrasts with the frequent assertion that population declines of many long-distance migrants are due to deteriorating conditions in non-breeding areas.

- Approximately half of the deaths were caused by people: primarily electrocution or collision with energy infrastructure; direct persecution (e.g. shot or trapped); and poisoning.

Addressing these threats throughout the species distribution, including migratory flyways, is essential for conserving Egyptian Vultures and many other migratory species, and is the aim of several projects with our partners. For example, tracking data from the LIFE Rupis project were included in the study at the same time as being used to inform local conservation measures in the Douro/Duero region of Portugal-Spain.

This paper arises from a large collaboration among 38 researchers from 12 countries, including from the Vulture Conservation Foundation (VCF) and builds upon another recent study by the same group that assessed Egyptian Vulture migration patterns at a cross-continental scale. This is a great illustration of how many people and projects are working together to identify the causes of vulture population declines, learning how to mitigate threats, and ultimately restoring vulture species to their former ranges. We are proud to be a part of this mission and thank all our partners for their ongoing efforts, and Evan, Ron and Steffen for leading this study!