A recently published study demonstrates the benefits avian scavengers contribute to people and the need to balance nature conservation and a sustainable economy.

Overview

Healthy ecosystems are crucial to human well-being. But how does a living nature contribute to people’s quality of life? Nature Contributions to People (NCP) have been classified into three main groups: i) material (e.g. food, energy, water); non-material (e.g. the effect of nature on mental health through recreational or inspirational experiences) and regulating contributions (e.g. pollination or carbon storage). However, non-material NCP are particularly difficult to assess. As a result, their importance has been undervalued for a long-time with negative consequences for society and the environment.

More recently, one of the most common ways to evaluate non-material NCP has been through economic evaluations of recreational activities. However, important species or guilds are often ignored in such evaluations. This is the case of vertebrate scavengers despite their crucial role in many ecosystem processes.

Scavengers provide non-material NCP through spiritual experiences, wildlife-based tourism or supporting personal identity (e.g. the pleasure from knowing that a particular species exists). Among the vertebrate scavenger guild, Old World vultures and condors have suffered severe declines in many of their populations. As a tool to reverse these declines, supplementary feeding sites (SFS) were implemented to improve food availability and decrease poison-related mortality. SFS have had a major role in improving the conservation status of vulture species, particularly in Europe. However, the economic benefits linked to the touristic value of SFS are increasingly considered over conservation reasons for establishing new sites. Surprisingly, the scale of these economic benefits has never been quantified previously.

Spain is a major destination for ornithological tourism in Europe and it hosts most of the European vulture population. This study, led by Ruth Garcia-Jiménez from the University of Lleida Spain, aimed at providing a much-needed economic evaluation of tourism activities associated with avian scavengers in the Spanish Pyrenees.

Methods

Data were collected between February 2018 and January 2020 following two stages. First, the authors conducted telephone interviews with managers of 53 of the SFS present in the Pyrenees. These interviews were aimed at collecting basic information on the management and structure of each SFS (e.g. mean number of visitors, price of entrance or the type of activities offered). In addition, 94 survey questionnaires were distributed among 9 SFS to gather information about travels, subsistence (food, lodging) and opportunity costs incurred by each visitor.

These data were used to calculate the mean visitors’ trip expenses. Combining these expenses with the mean annual number of visitors per SFS, the authors finally estimated the annual expenses associated with the tourism activities associated with avian scavengers at the Pyrenean SFS.

Results

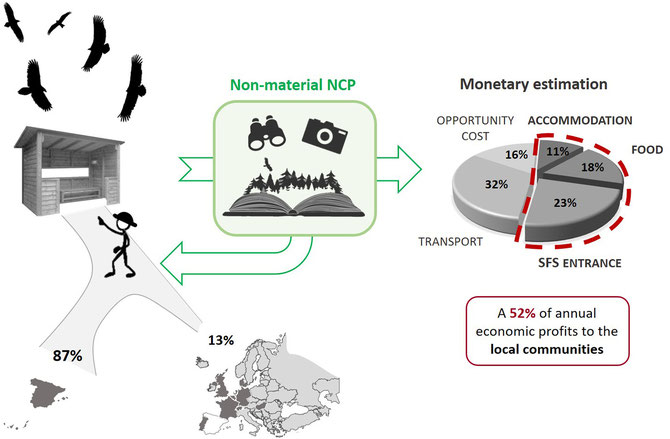

The authors estimated that expenses linked to recreational and educational activities at SFS reached an average of US $4.90 ± 2.67 million annually. This total amount consisted of 32.13% in travel expenses, 22.93% in SFS entrance fees, 10.78% in accommodation expenses, 17.92% in food expenses, and 16.24% in opportunity costs (see Fig. 1). This highlights that US $2.53 ± 1.36 million (52% of the total annual economic profits) are estimated as direct economic benefits to the local population.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The results revealed that tourism activities linked to avian scavengers at Spanish feeding sites alone provide a relevant income (almost US $5 million per year) to the Pyrenean community. This is a significant amount given that the estimated national expenses derived from all nature-based tourism activities in Spain were on average US $10.5 million in 2017.

Interestingly, SFS providing educational activities had a higher annual income than those offering only photographic activities. This was explained by the higher annual number of visitors those SFS received. In this context, these sites have an important role in providing both benefits to the local economy and non-material learning and inspirational contributions to people.

Recent research has estimated the economic benefits arising from the regulatory contribution of vultures to human health and well-being (e.g. rabies prevention in India). Yet this is the first study of this type focusing on non-material contributions in Europe. Further research is needed to better understand the societal benefits associated with the presence of healthy populations of avian scavengers.

The authors also highlight the importance of remembering that SFS are not designed for tourism but to help temporarily the recovery of avian scavenger populations. Therefore, the original conservation aim of SFS should always be prioritized as they can negatively affect vulture populations in certain contexts (e.g. spatial aggregation of territories and decreased breeding output of Pyrenean Bearded Vultures).

This study contributes to improve our understanding of how SFS, if properly managed, can benefit vulture conservation, provide educational and recreational benefits to tourists while injecting a significant income to the local communities. Finally, we believe at the Vulture Conservation Foundation (VCF), that communicating how wildlife conservation can promote economic development is a powerful tool to shift attitudes towards neglected or unloved species of conservation concern.

Source:

García-Jiménez, R., Morales-Reyes, Z., Pérez-García, J., & Margalida, A. (2021). Economic valuation of non-material contributions to people provided by avian scavengers: Harmonizing conservation and wildlife-based tourism. Ecological Economics, 187, 107088. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.107088