Although all vulture species can travel long distances, including migratory movements by Cinereous and Griffon Vultures, the Egyptian Vultureis Europe’s only true long-distance migratory vulture species. While most individuals from mainland Europe migrate from their breeding grounds in autumn to spend the winter in Africa, several island populations are non-migratory. There is also an increasing number of individuals that do not migrate but remain in Spain throughout the year. A recently published study provides new insight into these individuals’ movement ecology following years of monitoring and analyzing the movements of the largest known wintering population of the species in mainland Europe.

Overview

Migration is an integral part of the annual cycle of many species. Even though it is often considered a strategy shared by entire populations or species, this is not the case. Partial migration is, in fact, the most common form of migration, exhibited by many animals, but particularly birds. Partial migration means that specific individuals overwinter within their breeding region while others migrate to reach wintering grounds far away.

It is crucial to understand the causes and consequences of migratory behaviour changes in a species to better predict population structure and dynamics like survival. Drivers of migration are well known and include seasonal changes in habitat and food availability. However, little is known about the consequences of changing from migratory to resident behaviour in species with overlapping breeding and non-breeding grounds, especially how individuals behave in these environments during winter.

In the case of the Egyptian Vulture, a research team led by Jon Morant and colleagues from Aranzadi Sciences Society, University of Extremadura, Junta de Extremadura, Icarus Estudios Medioambientales and the University of Valencia aimed to fill some of these knowledge gaps by studying the spatial ecology and resource use of the species’ unique wintering population in south-west Europe.

Methods

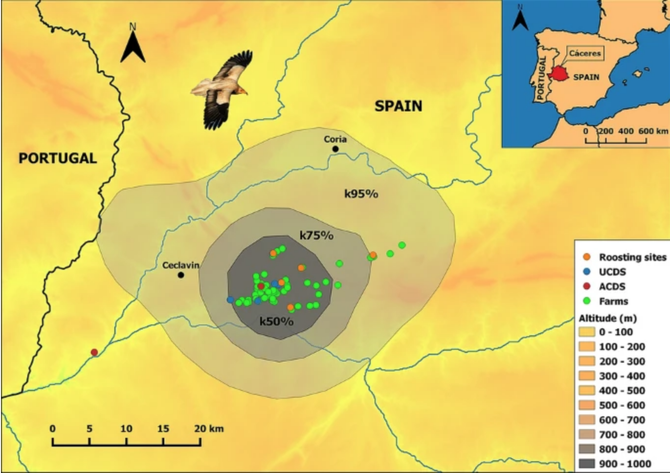

The research team combined field surveys and GPS tracking data from 12 birds between December to February during four wintering seasons 2014–2018 to describe the movement ecology of Egyptian Vultures’ largest wintering population in south-west Europe, located in Cáceres (Extremadura, Spain).

Results

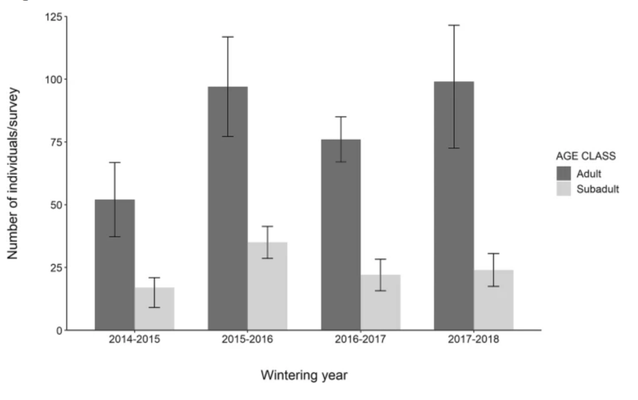

On average, the wintering population consisted of 85 individuals (range 58–121; 76% adults and 24% subadults), which congregated in five close roosting sites located near farms as well as authorized and unauthorized carcass deposition sites. It was not possible to conclude whether the population comprises subadults that do not migrate and then remain, or adults that opt to not migrate even after several successful migrations.

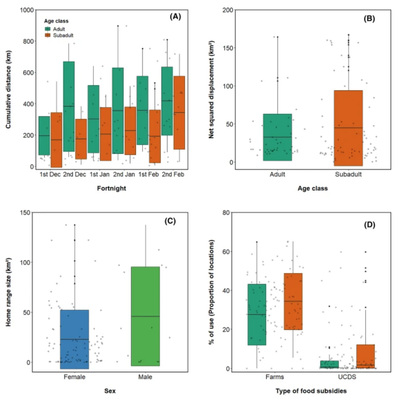

The results further illustrated that the Egyptian Vultures tend to remain close to the roosting sites, with females exhibiting smaller home range sizes than males, suggesting a different use of food sources. Overall, birds relied more on farms for food compared to other available food resources, especially subadult individuals.

The resource selection analysis revealed that the best predictors of space use at the population level were food availability, specifically goat and cow density, and land-use variables such as forest and agriculture lands to a lesser extent. Interestingly, Egyptian Vultures avoided areas with high density of sheep, pigs and variables related to human disturbance and artificial surfaces.

Conclusions and recommendations

According to this study’s results, the mainland Egyptian Vulture populations should be reclassified from migratory, except insular resident populations, to a facultative partially migratory species.

The authors hypothesize that, considering the increasing number of threats affecting Egyptian Vultures in their African wintering grounds, and the dramatic decline of vulture populations in the continent, a shift from a migratory behaviour to a sedentary one could positively influence the species’ European population in the long run. However, we still lack clear evidence about how Egyptian Vulture mortality varies across their range and this is the subject of an ongoing study.

Since the findings show that Egyptian Vultures congregate in significant numbers at roosting and feeding sites throughout the winter period in south-west Spain, these sites should be given some level of legal protection and regular monitoring to protect the increasing number of non-migratory individuals.

Furthermore, it is important to continue to assess the species’ movement patterns, foraging ecology and the use of protected areas to help understand the susceptibility to different threats and better inform conservation measures.

The Vulture Conservation Foundation (VCF) is contributing to this through the LIFE Rupis project and through cross-continental collaborative research with many partners, as demonstrated by the recent publication of the migratory patterns of individuals from several different breeding populations. From these results and previous publications, it is clear that a whole flyway approach is needed to conserve Egyptian Vultures, and our colleagues working on the Egyptian Vulture NEW LIFE project are working hard towards this for the Eastern Flyway.

Source

Morant, J., Abad-Gómez, J.M., Álvarez, T. et al. Winter movement patterns of a globally endangered avian scavenger in south-western Europe. Sci Rep 10,17690 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-74333-0