Once found only in the skies over Africa, the Critically Endangered Rüppell’s Vulture is now increasingly turning up in Europe. Two recently tagged individuals, tracked via GPS, have just made the journey across continents, however, with two different outcomes.

Tagged in Morocco, soaring into Europe

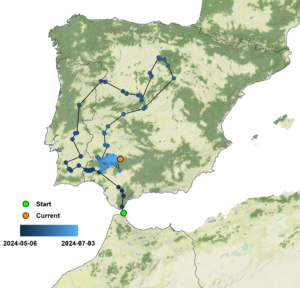

On 2 May 2025, a young Rüppell’s Vulture (Gyps rueppelli)—known as GR70—was fitted with a GPS transmitter at Jbel Moussa in northern Morocco, by colleagues based there. The tag, supplied by the Junta de Andalucía, is part of a broader effort to understand the species’ movement patterns in more detail. Just over a week later, on 10 May, GR70 crossed the Strait of Gibraltar into Spain, paused briefly in the southwest of the country, and has since continued its journey into Portugal.

GR70 is one of twelve Rüppell’s Vultures that has been tagged since 17 April, with ten of them carrying GPS transmitters. At present, one tagged bird remains in Portugal, another in Spain, while the others are still in Morocco, and never crossed into Europe. Researchers are tracking their movements closely—each flight path revealing more about where these birds go, how is their progressive colonization of Europe, and which threats they face along the way. This kind of information is essential for shaping future conservation plans that work across national boundaries.

Risky travels led to a sad outcome

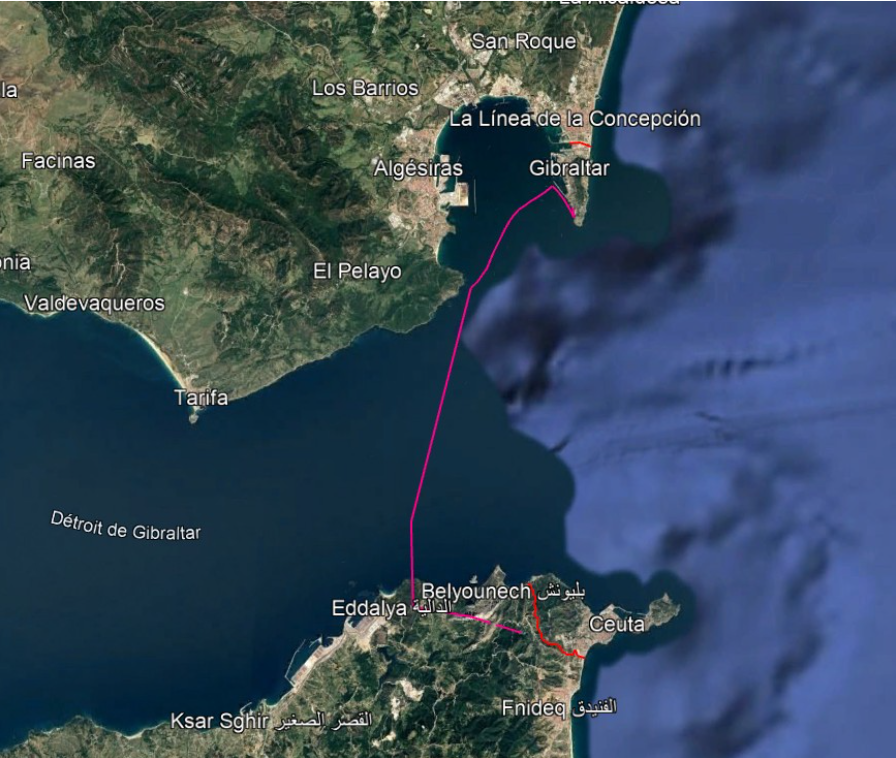

On May 12th, another young Rüppell’s Vulture, GR67, also tagged with a GPS transmitter, attempted to cross the Strait of Gibraltar at too low an altitude of 380 metres, while the typical altitude of vultures for such crossings ranges around 1000 metres.

He then arrived at Punta Carnero in Algeciras Bay at 1 meter altitude after travelling 18 km in just 1 hour, which was an abnormal sign. What likely happened is that GR67 lost altitude while flying over the open sea, had to flap its wings continuously to stay airborne—exhausting itself—and ended up falling into the water. Upon reaching the Spanish coast, it may also have been harassed by seagulls and forced to change direction toward Gibraltar, which disoriented the bird further.

After the incident, local ornithologists from southern Spain and Gibraltar coordinated to attempt a rescue. A boat was dispatched from Algeciras, but no trace was found. Sadly, GR67’s body was discovered the next day on a small beach in Gibraltar and recovered by local authorities.

Why tracking matters

Native to the Sahel and East Africa, Rüppell’s Vultures are facing serious declines. With an estimated global population of just 22,000 individuals, the species is listed as Critically Endangered by the IUCN. Major threats include habitat loss, poisoning—particularly from toxins like carbofuran—, killing for belief-based use. and a shrinking supply of carrion.

As obligate scavengers, these vultures are vital for keeping ecosystems clean and balanced. They likely prevent the spread of disease by consuming dead animals that would otherwise linger and rot. Their ongoing and rapid disappearance will likely affect not just biodiversity, but also people and livestock health.

That’s why tracking their movements matters. GPS data gives conservationists a clearer picture of where the birds travel, where do they eat, where they breed, and where they face danger, and where protection efforts should be focused. Insights from birds like GR70 help guide conservation strategies that span entire regions and continents.

A new pattern: Rüppell’s Vultures in Europe

It is no longer rare to spot Rüppell’s Vultures in Europe. In recent years, they have become more common in Spain, Portugal, and other parts of southern Europe—often seen flying alongside their close relatives, the Griffon Vultures. Scientists are still working to understand why this is happening, but shifting climate patterns, changes in food supply, and evolving migratory behaviour likely play a role. It is now accepted that Ruppel´s come to Europe amongst the many juvenile griffons that winter in west Africa, and that then attract their African cousins on their journey back home to Europe. A certain percentage of 1st year Griffon Vultures do cross into Africa.

This progressive colonization underlines the importance of international cooperation. Conservationists are now working more closely than ever across borders to track these birds, learn more about their needs, and ensure they are protected both in Africa and in the places where they are now increasingly turning up in Europe.

Cross-border conservation in action

The recent tagging project reflects this growing cross-border commitment. It brings together partners from Morocco, Spain, and Portugal, including the CRV Jbel Moussa, AMPOVIS, Junta de Andalucía, IUCN Centre for Mediterranean Cooperation, GREFA, and the Vulture Conservation Foundation (VCF).

At VCF, the focus is now on closely monitoring the presence of Rüppell’s Vultures in Europe. By fitting more individuals with GPS devices, the team hopes to better understand not only their origins and travel patterns, but also how long they remain in Europe and how they interact with local ecosystems.

Each bird adds a new layer to the story and the data collected is helping to shape a future where Rüppell’s Vultures can continue their remarkable journeys—safely soaring between continents. We are now expecting to confirm the first successful breeding of the species in Europe – so far a number of mixed pairs (with griffons) have been identified, including successful mixed reproduction.