New research led by Eneko Arrondo (Donana Biological Station-CSIC) and Ana Sanz-Aguilar (Animal Demography and Ecology Unit, IMEDEA CSIS-UIB and Applied Zoology and Animal Conservation Group, University of Balearic Islands) indicates that survival rates of adult Griffon Vultures were lower in landscapes that are more modified by human activities.

Research Overview

Between 2014 and 2016, the researchers fitted tracking units to 30 adult Griffon Vultures in southern Spain, captured in the Sierras de Cazorla Segura y las Villas Natural Park, and 36 to adult Griffon Vultures in northern Spain in the Middle Ebro Valley. The northern landscape is characterised by more intensive farming practices and increased density of human infrastructure (e.g. power lines, roads, rubbish dumps). In contrast, the southern landscape consists of more extensive farming practices in “dehesa” (agro-forestry) habitat, where traditional sheep farming, game hunting, forestry and tourism dominate in terms of land use.

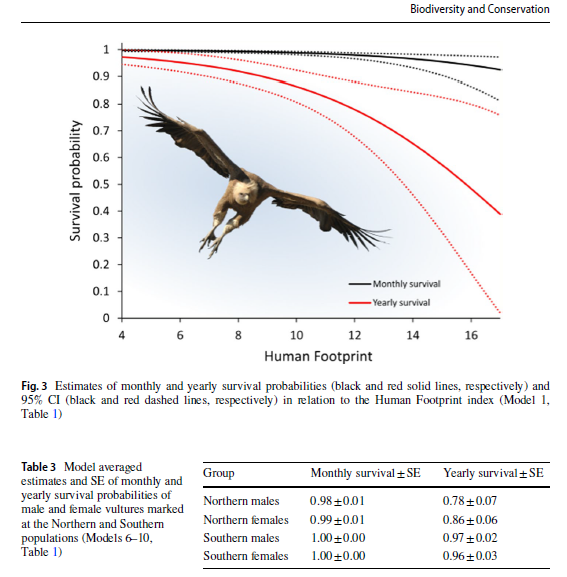

The authors assessed the level of human modification (termed “anthropisation” in the article) in the areas that each vulture used for their regular daily activities by calculating the average “Human Footprint” index within each individual’s home range. The Human Footprint index provides a measure of the density of the human population and settlements, electric power infrastructure, intensive agriculture lands and transport infrastructure, at a 1 km2 scale. They then investigated how survival probabilities (calculated using known-fate capture-recapture models) of each individual were influenced by this index, the population they were captured from and their sex.

Results

The results showed that vultures from the northern population occupied larger and more human-modified home ranges than those from the south and that survival rates for the northern population were significantly lower.

As the figure shows, annual survival rates decreased with increasing levels of human modification of the landscape. This is emphasised by the disparity in the number of vultures that were found dead during the study. From the northern population, 15/36 (~42%) tracked vultures were found dead, compared to 3/30 (10%) in the southern population, which is reflected in the much lower survival rates: 0.82 probability of surviving for one year in the northern population, compared to 0.97 in the south. It is important to note that the survival rates of the northern population are also lower than other studied Griffon Vulture populations, indicating that the population may be at risk from elevated adult mortality rates.

Interestingly, the analysis also found a small effect of the sex of each individual on their survival probability, with males in the northern population apparently more at risk of mortality than females. However, the authors encourage further research into this aspect, particularly as there was no difference found between males and females from the southern population.

The main mortality causes were all non-natural: collisions with vehicles (33.3%), poisoning (27.8%), electrocution (22.2%) and collision with wind turbines (11.1%). This once again emphasises the importance of mitigating these threats not only in areas with small, extinction-prone populations of vultures, but also in countries such as Spain, where vulture populations are thriving nationally but might still be susceptible regionally or locally due to elevated mortality rates. The authors promote the importance of less-modified landscapes, particularly dehesa habitat, as well as maintaining traditional extensive farming practices and wild ungulate populations for vulture conservation and general ecosystem integrity.

This important and neat piece of research demonstrates how tracking data can be used in combination with other spatial data to reveal patterns of vulture mortality, identify the main threats, and ultimately inform the implementation of effective, targeted conservation strategies. It will be fantastic to see similar research for the three other vulture species, perhaps at a Europe-wide scale. Congratulations to Eneko Arrondo, Ana Sanz-Aguilar and their co-authors for this publication!

Never miss any vulture news by signing up to our newsletter.