Condors and vultures (hereafter “vultures”) are threatened necrophagous bird species relying on the consumption of medium to large-sized mammal carcasses. In large parts of their distribution range, vultures feed mostly on the carcasses of domesticated ungulates. This makes them vulnerable to changes in farming practices or conflicts with rural stakeholders.

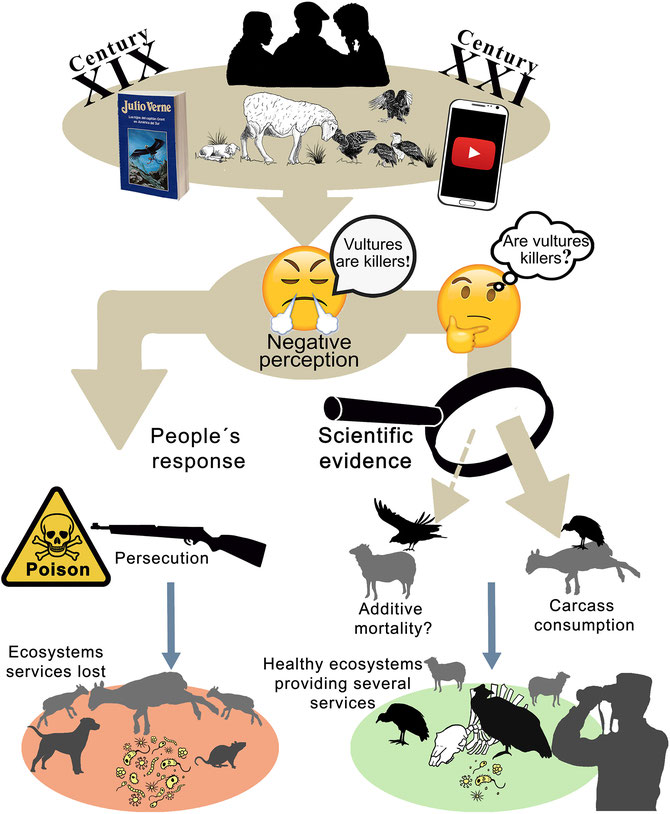

A surge in perceived conflicts between farmers and vultures has been recently observed worldwide. This situation arises from biased observations and misinterpretations of vulture predation events on livestock. Misinformation spread by media platforms can be a threat to biodiversity conservation by amplifying human-wildlife conflicts and illegal persecution of protected species.

This article led by Dr. Sergio Lambertucci from the National University of Comahue-CONICET, Argentina, highlights the danger of spreading speculative stories for the conservation of threatened vultures and suggests potential pathways to alleviate this conflict.

Vultures are not predators

Vultures have evolved morphological, physiological, and behavioural adaptions that make them extremely efficient obligate scavengers. However, they are inefficient at killing living prey, but occasionally, some vulture species have been reported to kill young, weak or injured animals. Rare livestock attacks have also been observed under specific circumstances (e.g. lambs left unattended).

Vultures contribute to healthy ecosystems and thriving societies

The presence of healthy vulture populations has benefits for ecosystems and human societies. For instance, the removal of carcasses by vultures saves millions of dollars per year by avoiding the collection, transport and incineration of dead livestock. Vultures can control the growth of pest species that feed opportunistically on carcasses by limiting food availability in the environment. This regulating role has clear benefits for human health as shown by the increase in feral dog populations and human rabies cases following the Indian vulture crisis. Finally, vultures also provide income to local communities through avian scavenger-based tourism and non-material contributions to people (e.g. by enhancing wildlife-human connections).

Yet vultures suffer from chronic negative perceptions

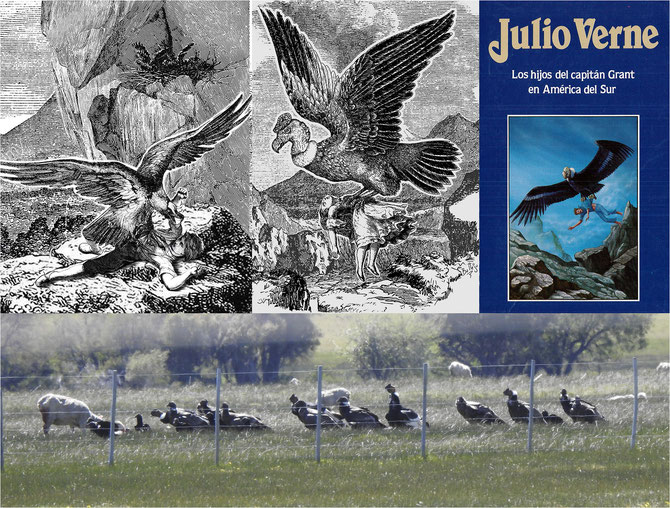

Vultures have suffered from misperceptions since the 18th century and have been often portrayed by popular culture as ‘malicious predators of livestock and even people’ over the last centuries. Negative attitudes towards this group of species resulted in institutionalized persecution and the extirpation of several vulture species from extensive parts of their distribution range.

These old negative perceptions have emerged again recently around unsustained claims of vulture attacks on livestock in several parts of Europe, but also in Africa and America. For instance, fake videos promoting the active role of vultures in livestock deaths have turned viral in Spain. However, in most cases, carnivores, mostly feral or domestic dogs, were responsible for the sheep attacks and vultures were observed feeding on post-mortem individuals.

The spread of such misinformation, including by conventional news media, has damaging effects in stakeholder communities by perpetuating and amplifying negative perceptions of vultures. Further research is therefore needed to understand if, when and why vultures contribute to additive livestock mortality (i.e. would these deaths have happened anyway due to poor livestock health or do they really result from injuries caused by vultures?).

The way forward

What can be done to prevent misinformation from overturning decades of conservation efforts? The authors suggest a science-based agenda in order to i) adopt a standardized recording protocol after livestock death (to evaluate the role of vultures in each loss); ii) training researchers, managers and other stakeholders to collect evidence; iii) better quantify and communicate the material and non-material contributions provided by vultures to people and weight the costs and benefits of vulture presence; iv) evaluate the extant of conflict between humans and vultures in different areas; v) assess the effectiveness of nonlethal deterrence strategies (e.g. the use of guardian dogs) in areas where additional mortality occurs.

Collection of scientific data should be accompanied by carefully planned communication campaigns. For instance, awareness-raising campaigns (like the ‘vulture awareness day’) in areas of high conflict could reduce the risk of misperceptions and ‘fake news’. Similarly, the transformative power of social media should be used to spread accurate information, while empowering influential stakeholders, e.g. pro-vulture farmers, could also help solving conflicts in local communities.

Increased collaboration between scientists, biodiversity NGOs, rural stakeholders, media and policy makers should urgently focus on reducing misinformation on vultures and restore the thousand-years-old mutual relationship between avian scavengers and farmers. Challenging negative perceptions towards vultures is an important part of our work at the Vulture Conservation Foundation and we highly congratulate the authors for this perspective article!

Source

Lambertucci, S., Margalida, A., Speziale, K., Amar, A., Ballejo, F., & Bildstein, K. et al. (2021). Presumed killers? Vultures, stakeholders, misperceptions, and fake news. Conservation Science And Practice, 3(6). doi: 10.1111/csp2.415