A new review article published in the journal Conservation Letters has identified that the majority of conservation science research articles published over the last 20 years have failed to contribute effectively to the main aims of the field – to arrest declines in biodiversity and prevent extinctions.

Although the overall message of the article is quite depressing, by confirming that there is often a mismatch between research and effective practical conservation action, it does illustrate that research has in fact been very useful for planning and implementing effective measures to conserve vultures in some parts of the world.

How to use research for effective conservation actions

The authors (David Williams, Andrew Balmford and David Wilcove) describe a simple framework for how research should progress to be more beneficial for informing and implementing effective conservation action. The process initially involves identifying conservation problems (e.g. declining populations) and diagnosing their proximate and ultimate causes (e.g. socio-economic factors driving negative perceptions of certain species, resulting in illegal killing), and then moves to proposing, designing and implementing actions, and eventually testing the responses of the target species or habitats.

However, the vast majority of the 959 articles published in 20 conservation journals over the last 20 years that were included in the review simply described the “state of nature” (e.g. this species declined by this much over this time period) or the mechanisms directly causing the observed changes, with very little research on designing or implementing conservation responses. The authors do not suggest that each article should address all of these steps at once, but that there should be a shift towards trying to understand the sources and drivers of change, as well as a much-needed focus on designing workable and socio-economically realistic interventions.

Vulture conservation used as best practice example

Fortunately there are examples of good practice of how researchers followed the framework to deliver effective conservation science, and vultures featured as a case study in the article. Specifically, the response to diclofenac poisoning, which caused the collapse of South Asian vulture populations, was used as a good example of how “successful mission-oriented conservation science did indeed follow this pattern.” The research sequence started by establishing that vulture populations had recently and rapidly declined; then identified the cause as accidental poisoning by diclofenac; then moved on to proposing, designing, implementing and testing a range of interventions such as captive breeding and providing safe food at vulture restaurants, identifying a safe alternative to diclofenac (meloxicam), and preventing the use of diclofenac for veterinary use. Continued monitoring then established that vulture populations had responded to these interventions, with declines slowing and some populations increasing.

This describes the history of the SAVE consortium – Saving Asia’s Vultures from Extinction – which can be read in full here, which also forms the basis of the Multi-species Action Plan to Conserve African-Eurasian Vultures and the other vulture conservation action plans that the VCF and partners have developed. It is not the first time that vulture research and conservation have been used as best practice examples, with an article published in 2019 highlighting the standardized and coordinated work done by the International Bearded Vulture Monitoring Network.

However, there is still a lot to learn about the diverse threats that vultures face during their daily activities, and, due to the vulnerability of vulture populations to any cause of increased mortality, it is essential to investigate all of these in order to implement effective mitigation measures. We hope it is clear from the regular research summaries posted on VCF’s website that there are many more examples of valuable research being done that directly informs vulture conservation strategies (for Egyptian Vultures for example), and the ongoing recovery of vulture populations across Europe are a testament to the great efforts made by researchers and practitioners working together towards shared goals.

Source

Williams, DR, Balmford, A, Wilcove, DS. The past and future role of conservation science in saving biodiversity. Conservation Letters. 2020;e12720. https://doi.org/10.1111/conl.12720

Figure 1

A research framework for conservation science. A simple framework suggesting how conservation research might progress if it is to deliver prescriptions for addressing real‐world problems. Initial characterization of the changed state of a population, community, or ecosystem needs to be followed by diagnosing the mechanism responsible (upwards sloping arrow). This then enables research proposing, designing, implementing, and testing responses to this threat mechanism (lower sloping arrow) and improving our understanding of it (lower horizontal arrow). However, depending on the nature and urgency of the threat, it is often desirable to establish the source of the threat and quickly develop and test responses to it, or to identify, and in due course respond to, the underlying driver(s) (dashed arrows).

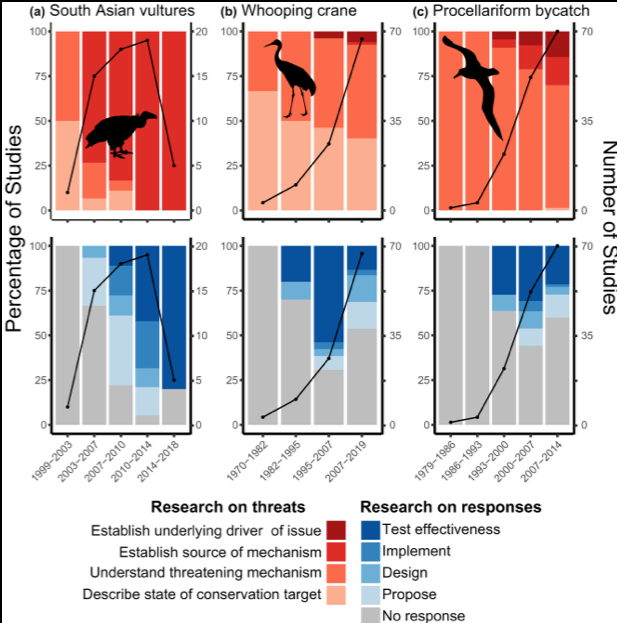

Figure 2

Research topics in selected case studies. The number of papers investigating (a) the South Asian vulture crisis, (b) whooping crane conservation, and (c) the bycatch of procellariform seabirds over time (black lines) and the percentage investigating different levels of threat and response (shaded bars). Image credits: Birgit Lang, Lauren Anderson and Ferran Sayol.